Who gets left behind in digital health?

Access, literacy, and equity are shaping the future of care. But not everyone can log in.

Your internet shouldn’t determine your health, but in today’s digital-first healthcare world, it often does.

I use tech for nearly every facet of my life: research, shopping, healthcare, exercise, socializing, entertainment. If I’m not on my desktop, I’m on my laptop. And once I shut that, I reach for my phone. Technology is seamlessly woven into my daily routine.

But that’s not everyone’s reality. It’s a privilege.

As a public health scientist, I think a lot about how technology influences health. I can make appointments, request prescriptions, and check lab results with a few clicks. COVID-19 accelerated this transformation through the rise of telehealth, and for some conditions—especially in mental health—it showed us how tech can increase access to care.

But here’s the problem: What happens to people without stable internet or the right devices? How do they participate in this transformed healthcare model?

There’s a term for this: the digital divide.

Roughly 42 million people in the U.S. lack access to broadband internet. And yet digital health continues to expand, assuming that everyone can participate.

I’ve been in the health tech space for the last two years and genuinely enjoy it. Many startup founders I meet are passionate about solving gaps in care. But this same issue keeps resurfacing: tech-forward solutions can unintentionally worsen disparities. Apps often require subscriptions, stable Wi-Fi, and digital literacy. And culturally, many digital tools aren’t built with marginalized communities in mind.

Technology has transformed healthcare, yes. But it hasn’t transformed it equally.

The rich get richer.

Telehealth is great if you can access it. Poor internet connectivity, no data plan, or limited tech access means missed appointments, misunderstood medical advice, and increased frustration. Imagine trying to have a 15-minute virtual appointment with a doctor, but the video keeps freezing. It’s inefficient and inequitable. These challenges disproportionately affect people of color, low-income communities, and medically underserved populations.

Without serious investments in infrastructure and inclusive policy, the divide will only widen.

Not everyone hears the message.

Public health campaigns are on billboards, online ads, push notifications…everywhere. But if you have limited digital access, you may miss out entirely.

There’s also the issue of digital literacy. My mom, for example, wouldn’t know how to schedule a doctor’s appointment online. Even if she had the device, the language barrier and interface design would likely turn the process into a frustrating obstacle.

So what can we do?

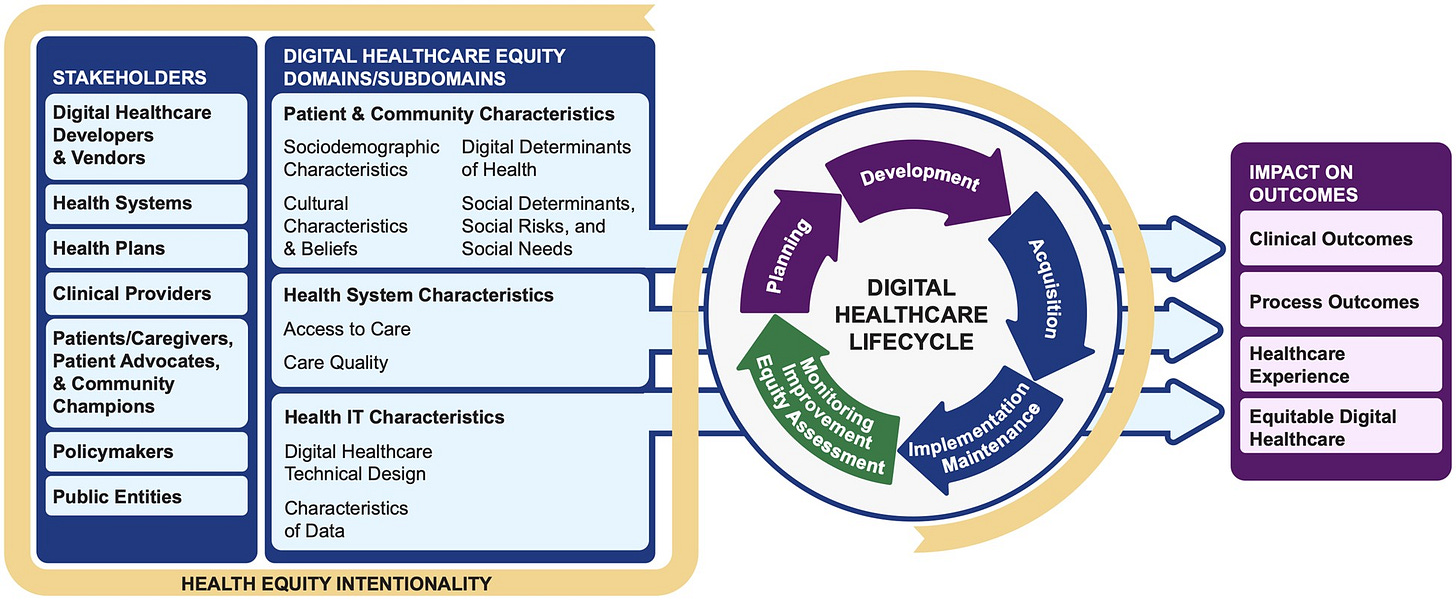

One helpful tool I’ve come across is the Digital Healthcare Equity Framework. It’s a way to evaluate equity across the digital healthcare lifecycle. Here’s the breakdown:

Three domains:

1. Patient & Community Characteristics

Sociodemographics (race, ethnicity, income, education)

Cultural factors (language, traditions, health beliefs)

Digital determinants (broadband access, device availability, digital redlining)

Social risks and needs (poverty, discrimination, neighborhood factors)

2. Health System Characteristics

Access to care (insurance coverage, transportation, provider networks)

Quality of care (culturally competent, patient-centered, linguistically appropriate)

3. Health Information Technology Characteristics

Technical design (user-friendliness, timeliness, privacy and security)

Data characteristics (accuracy, transparency, representation, justice)

Stakeholders—including clinicians, health plans, product developers, caregivers, and patients—must actively collaborate across all three domains. Equity isn’t just a checkbox but something that needs to be embedded from the start.

The Lifecycle

Digital healthcare moves through a cyclical process:

Planning → Development → Acquisition → Implementation → Maintenance → Monitoring/Equity Assessment

Each stage offers opportunities to pause, assess, and improve. Done well, this leads to better outcomes, better experiences, and fairer digital healthcare for everyone.

A tangible example: The Oura Ring

Let’s apply this framework to the Oura Ring, a wearable that tracks sleep, activity, temperature, and more. Some users now rely on it for ovulation tracking to support family planning. The ring syncs with an app, offering insight into cycle patterns using changes in temperature and heart rate variability.

For someone like me with stable Wi-Fi, a smartphone, and digital fluency, it’s a seamless way to monitor reproductive health. But apply the Digital Healthcare Equity Framework, and gaps emerge:

Patient/community: What about users whose primary language isn’t English? Or those unfamiliar with biometric tracking?

Health system: Are healthcare providers trained to interpret or trust data from the Oura Ring? Does the tool integrate meaningfully into care plans, or does it live in a silo?

Tech characteristics: Is the app intuitive for first-time users? Does the data reflect diverse populations, or is it normed on narrow groups? What about those who can’t wear the ring at all times due to their job requirements?

The Oura Ring is an exciting example of consumer-driven health innovation. But without thoughtful integration and equity checks, it risks serving only the digitally privileged.

Technology is changing healthcare. But if we don’t design for equity from the beginning, we’re just building new barriers in more expensive packaging.

this is so important to raise awareness about! it also makes me wonder what other areas the digital divide is impacting, if we keep focusing on technology-based solutions to various problems

this was an interesting read. never thought about the 3rd and 4th order effects of digitizing so much that is necessary